On April 5, Chinese rights lawyer Wang Quanzhang, the last lawyer of the group convicted during China’s 2015 infamous “709” crackdown, will be released from prison since his detention in July 2015. He is unlikely to be a free man, however.

I’ve used “Non-Release Release” (NRR) to describe the phenomenon of individual rights activists and lawyers in China often being released from prison into other, nominally “free” forms of what amounts to detention, such as de facto house arrest or enforced return and restriction to their native village. But NRR can also be used for large numbers of ordinary people, such as Muslims in the Xinjiang region. Many Uyghurs and other minorities there have reportedly been released from “re-education center” prisons, only to be forced to work in factories in various places.

NRR is nothing new in China. It came into use as a system at least as early as the Communist Party’s infamous “anti-rightist campaign” of 1957-58 when the government promulgated regulations that formally authorized the notorious, supposedly non-criminal, punishment of “reeducation through labor” (RETL). In providing for eventual release from RETL’s forced labor camps, the regulations permitted the police to keep on the labor camp premises, after their formal release, those prisoners who had no fixed abode, job or family awaiting them.

I knew, for example, an Indonesian Chinese who had studied law in China in the mid-1950s, served briefly as one of the new Soviet-style lawyers that Beijing had introduced during a brief liberalizing experiment, and was then rounded up for RETL in remote Xinjiang in 1958. He was “released’ in 1961 at the end of his three-year sentence but forcibly kept for another two decades at the same isolated work camp where he had been confined, ostensibly because he had no family in China to which to return. Although he was paid slightly more than when detained under RETL, he was actually forced to provide the regime with cheap labor in a part of China where most people did not want to work. Obviously, this arrangement was also a type of stability maintenance, political control.

The NRR system has evolved continuously, of course, over the years despite the formal termination of RETL in 2013. By then the police had acquired a lot of experience keeping under continuing control people who had been formally released after completing criminal sentences or even after being detained by the criminal process without ever being convicted or after having been “merely” detained under RETL or similar supposedly “non-criminal” sanctions. One could even say that former Party chief and Premier Zhao Ziyang became a victim of NRR, since, after being toppled just before the massacre of June 4, 1989, he was informally but effectively confined outside of prison — in the Party leadership’s comfortable living quarters — for the last 16 years of his life!

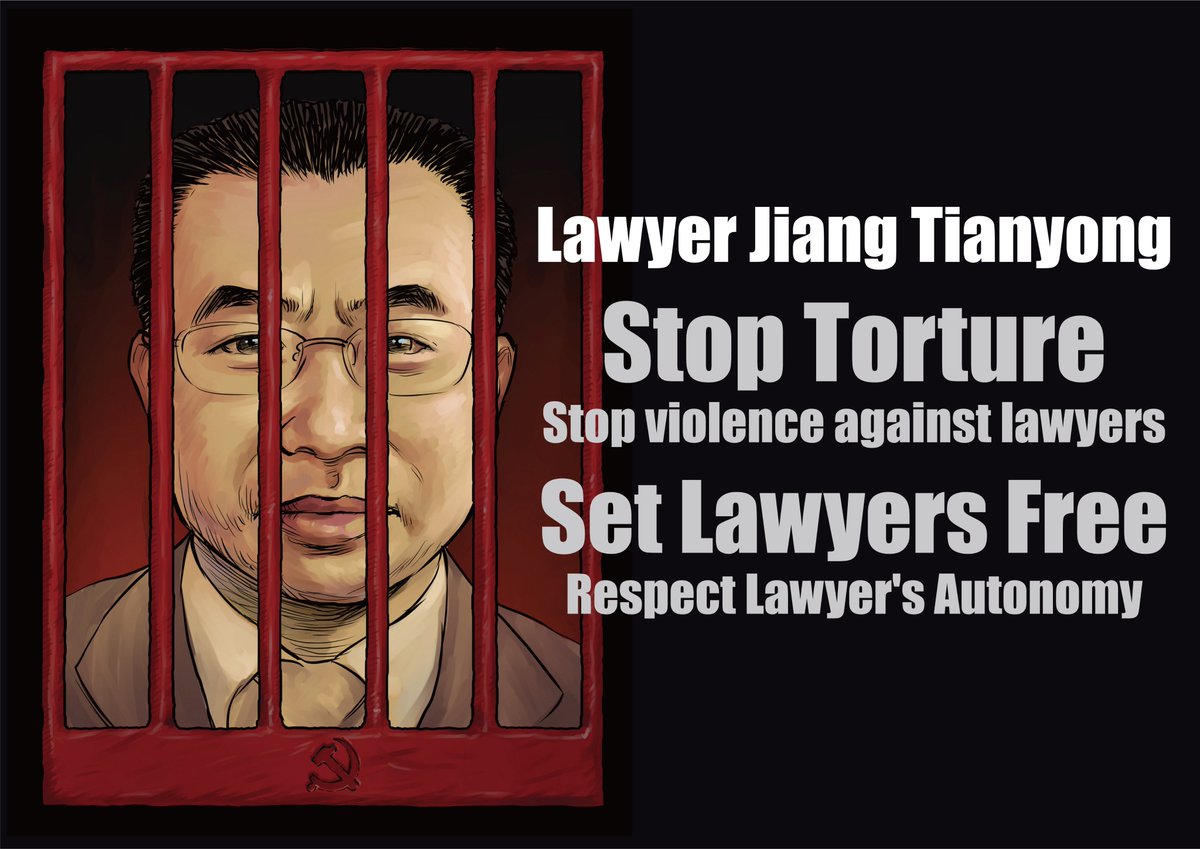

In the past decade NRR has been customized to suit the Party’s needs for effectively suppressing human rights lawyers on a more individualized basis than a formal system might allow, and also for a longer time than formal criminal or administrative sanctions might seem suitable. To the public, NRR looks better than sentencing a lawyer to life in prison, but it can nevertheless amount to a more discreet form of stifling someone forever. For example, whatever became of the great, courageous lawyer Gao Zhisheng? While repeatedly subjected to the formal criminal punishment system, his resistance generated periodic bad publicity for the Party and government. Since his last “release”, however, which forced him back to his native village, he has disappeared. Do people still remember him? Many wrongly assume he has happily been “reformed”.

Think blind “barefoot lawyer” Chen Guangcheng, who, after four years in prison, was “released” to his rural farmhouse with a couple of hundred thugs guarding him around the clock until his miraculous 2012 escape to the American embassy.

What will Wang Quanzhang’s “release” on April 5 amount to? It might have been more appropriate to release him on April Fool’s Day!