My hope, rather vain in the current political climate, is that Jiang’s case will ventilate the problem of “residential surveillance” so thoroughly that it will create pressure for reform, as did Ai Weiwei’s case in 2011. At that time, if the government’s target maintained a residence in the jurisdiction of the police, the police were forbidden by Ministry of Public Security (MPS) rules to detain him in any residence but his own, i.e., to restrict him to genuine house arrest. What the police often did, however, as in Ai’s case, was to detain suspects they deemed undesirable in places designated by the police that were neither suspects’ homes nor regular police detention houses that, whatever their failings, were at least regulated by normal criminal procedures and protections. This was a plain violation of MPS regulations if the suspect maintained a local residence.

As a result of the Ai case and others that resulted in protests, when the CPL was revised in 2012 a specific provision was inserted into the new code authorizing RS “at a designated location”, i.e., in police custody, even in cases where the suspect maintained a local residence, but limiting this new authorization to three circumstances, i.e., cases involving national security, terrorism or serious bribery. As is so often the case, the relevant legislative language is vague, especially the provision that permits police to impose this six-months incommunicado sanction whenever they decide that the suspect may have committed a crime related to “national security”, an exercise of discretion that, unlike their desire to formally “arrest” someone, which must be approved by the procuracy within a 37-day period, the PRC system does not permit any other agency to review. Thus, as in Jiang’s case, all they need to do to inflict RS is assert a suspicion that the case might involve some aspect of national security.

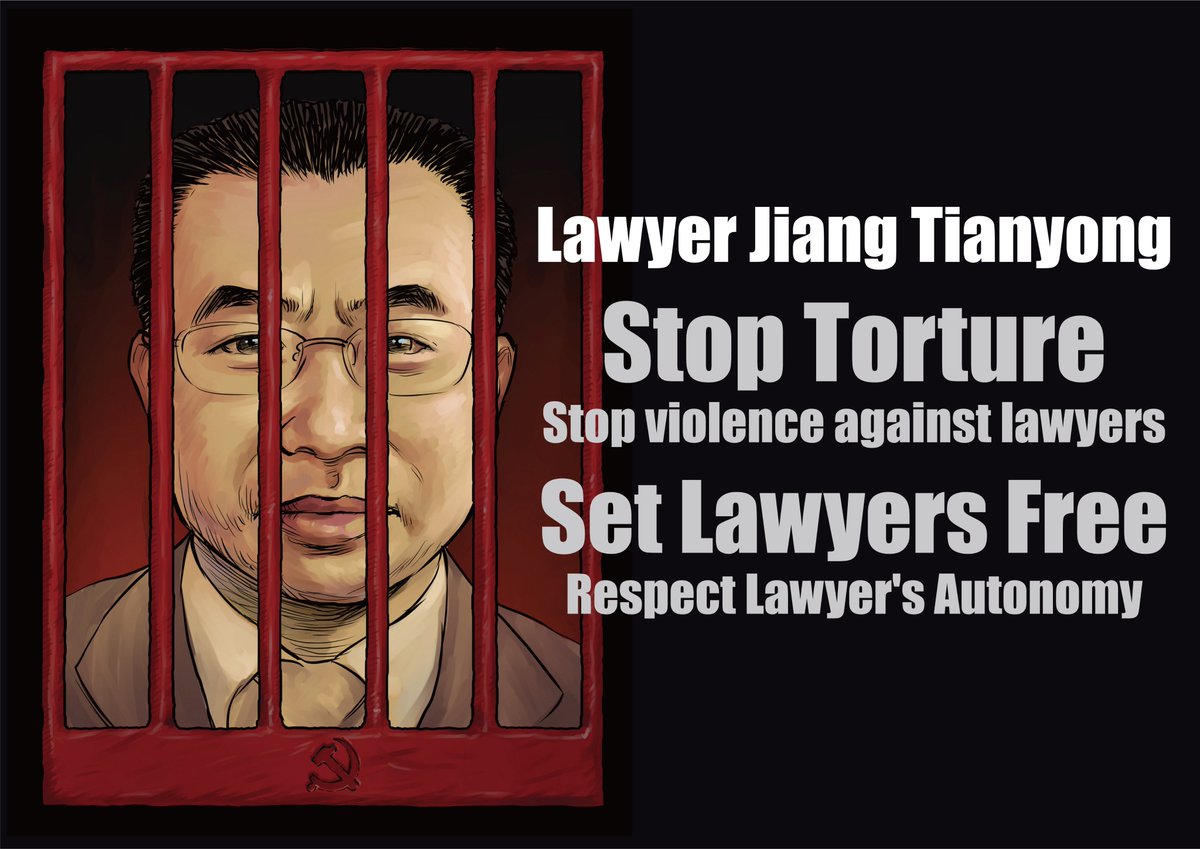

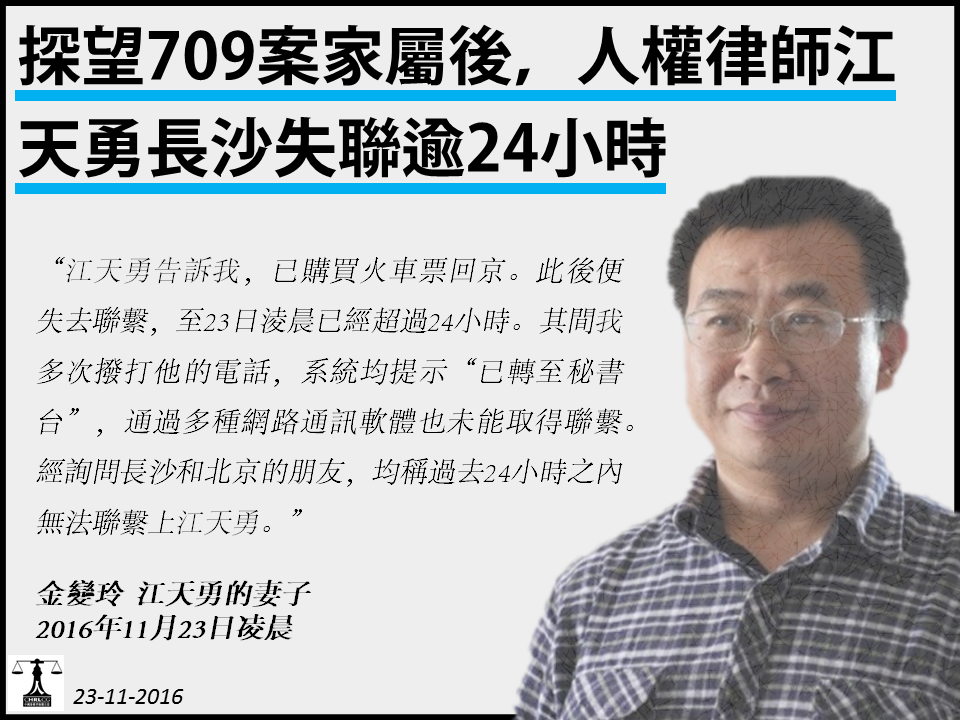

Without even meeting any standard such as “probable cause” to believe the crime was committed by the suspect, the police detained Jiang ostensibly because he might have “incited subversion of State power”. This gives the police six months, without interference from any lawyer, family, friends or media, to subject the suspect to a whole range of pressures and punishments including torture in a highly coercive, sealed-off environment.

At the end of that very long period the police decide, based on the suspect’s degree of “cooperation” as well as other factors, whether the evidence elicited via their techniques warrants criminal prosecution in accordance with prescribed procedures leading to “arrest”, indictment, trial, conviction and sentencing. The final formal charge may indeed claim a violation of “national security” such as “subversion of State power” or merely “incitement” to such subversion. But the charge may turn out to be for a lighter offense the long incommunicado investigation of which would not have been authorized by the RS legislation.

So was the 2012 revision a reform? On the one hand, it prohibits police from giving RS in a “designated location” to a local person suspected of tax irregularities, for example, as Ai Weiwei supposedly was. On the other, it now for the first time authorizes incommunicado RS for local people any time the police choose to investigate conduct they wish to claim might constitute a type of “national security” violation (or a serious bribery or terrorism-related case). The result is that police, and the Party, now enjoy virtually unlimited freedom to arbitrarily detain and punish for six months anyone they think may be a dissident. This needs to be kept in mind when considering the progress made by the formal abolition of the police administrative punishment of “reeducation through labor”.

It should also be pointed out that Party members, who are subject to the feared Party “discipline inspection” procedures of “shuanggui”, which can extend incommunicado detention for longer periods than RS, are not immune from RS either, although it would take unpermitted empirical research to determine how often this type of RS is used against them.