On Tuesday, October 3, 2017, retired Cardinal Joseph Zen of Hong Kong came to NYU Law School to take part in the weekly dialogue on Asian law and society of the US-Asia Law Institute. For over an hour, in an informative and lively session, Cardinal Zen answered questions from me and other USALI colleagues and students concerning the plight of the 12 million Catholics in Mainland China and the long-running negotiations over the normalization of relations between the Vatican and the People’s Republic of China.

Wu Gan’s “Trial”—Yet Another Sad Example of China’s Political “Justice”

Wu Gan has been for many years one of the leading and most-admired human rights activists in China. After criminal detention for over two years he will finally be brought to “trial” August 14 in a secret proceeding.

Wu Gan’s pre-trial statement is surely one of the most moving and accurate descriptions I have read of the Chinese government’s manipulation of its legal system to stamp out freedoms of expression. This account of his personal experience encapsulates virtually all the abuses that the Xi Jinping regime has been committing against human rights activists and their courageous lawyers. It is tragic testimony to the pathetic attempts of the Communist Party to drape its oppression in the mantle of “law”. To me the saddest aspects are its reminder of the forced collaboration of China’s judges with its police, prosecutors and Party legal officials in suppressing the constitutionally-prescribed rights and freedoms of the Chinese people.

Wu Gan’s statement ranks with those of China’s greatest martyrs to the cause of democracy, human rights and a genuine rule of law, including the late Liu Xiaobo. It will inspire those few activists inside and outside the country who still dare resist the current onslaught. Unfortunately, because of the regime’s monopolization of the media, its message will not be seen by most Chinese. Nor is it likely to be noticed by much of an outside world distracted by too many crises closer to home.

Wu Gan's pre-trial statement in Chinese, source: China Change.

Hong Kong Government Seeks Harsher Sentence for Democracy Activists

Left to right: Joshua Wong, Nathan Law and Alex Chow, outside Eastern Court in August 2016. Photo: Sam Tsang/SCMP

The Hong Kong Government is pressing the judiciary for much harsher sentences for Joshua Wong, Nathan Law and Alex Chow. Immediate imprisonment and 5-year disqualification from office are likely.

The court case against these leading activists has just taken a turn that surprised the accused. The Hong Kong Department of Justice, dissatisfied with the original court sentence to “community service”, appealed for a much harsher, immediate prison sentence. Defendants may now get sentenced to between two and six months by the appellate tribunal. The length of the sentence is crucial not only because of the duration of the physical and mental punishment inflicted but also because a sentence of three or more months will disqualify the convicted from standing for office for the next five years! Hong Kong’s judges are coming under increasing political pressure. The outcome in this appeal will tell us more about their response.

Beijing is going all out to destroy the democracy movement and the Hong Kong courts are increasingly under pressure. Those who haven’t seen the Netflix video “Joshua: Teenager versus Superpower” may want to do so before the outcome, which is imminent. In October Joshua may be marking his 21st birthday in prison!

Liu Xiaobo’s death

Liu Xia holds a portrait of Liu Xiaobo during his funeral. AP: Shenyang Municipal Information Office

The propaganda struggle over Liu Xiaobo’s demise was a sad but fascinating spectacle. The PRC’s distorted video broadcast of his medical examination was a ghoulish sight as well as a horrible invasion of his privacy and violation of arrangements made with the German government. The truncated, swift and restricted funeral arrangements were a farce.

Yet, as some observers have come to recognize, if only as inadequate consolation, the extraordinary circumstances of this Nobel laureate’s departure may prove his greatest contribution to the cause of free speech he so gallantly served. Liu’s final tragedy has alerted the world, to an extent even greater than did the empty chair in Stockholm, to the Chinese Communist Party’s inhumane oppression.

Despite the enormous international pressures on Xi Jinping, China’s ruthless leader insisted on Liu’s last pound of flesh. Xi was bent on heartlessly punishing Liu to the end for following the admonition of Xi’s own father, a famous first generation Communist leader who, after suffering 16 years in political exile, urged the Party to allow freedom of speech not only among the elite but also for all Chinese people. Today in China such advice constitutes “incitement to subversion.”

In terms of its immediate impact, Liu’s death has energized human rights activists outside China, at least for a time. Unfortunately, however, I don’t think his death will have a major favorable impact on human rights activities inside China, since he had already been silenced for a long time and most people in China don’t know about him, at least in a positive way. To the extent people do know about him and care, many will be further intimidated by his fate, while some others may be inspired to enter the human rights field, if only cautiously.

On the surface the human rights/political reform movement in China is in dreadful shape. It obviously has got this way because of extraordinary massive, ruthless and efficient repression that has understandably deterred the many liberal elements in Chinese society and government. Yet, quietly, quite a lot of professional legal reforms are still under way. They do not affect the many political prosecutions that take place or the unauthorized, illegal restrictions that are indefinitely imposed on human rights activists, outside the formal legal system, by police and their thugs. But they gradually improve procedures in ordinary criminal cases and lay the groundwork for more comprehensive reforms to occur when the political climate becomes less repressive, as it may well after Xi Jinping’s eventual departure from office.

Human rights issues will not disappear from the media with Liu. The cases of his wife Liu Xia and just released from formal prison Xu Zhiyong will highlight what I call NRR – “Non-Release ‘Release’”, another, lesser-known but insidious form of oppression. These are home prisons of an indefinite duration, and they restrict not only the activists but also their families, relatives and friends. Usually there is no legal authority for such repression. Ask Cheng Guangcheng, Gao Zhisheng, Li Heping and Li Chunfu, for example, or their families! There are too many examples.

When Liu Xiaobo was treated in the hospital, Chancellor Angela Merkel called upon the Chinese government in vain to release him to go abroad for his final moments “as a signal of humanity”. Can we expect foreign governments to do more? Will they be more effective? Many governments feel that their human rights protests against Beijing will have no positive impact on the PRC and will have a negative impact on other aspects of their relations with China. To the extent they do protest, it is often more a response to their own citizens’ pressure for action than to genuine concern for human rights, and their domestic business constituents usually have more clout than their human rights community. Compassion fatigue and realistic hopelessness about the Xi Jinping regime are also factors.

Yet those of us on the outside have to persist in our efforts to directly influence developments in China and to put pressure on our own governments not only to influence China but also improve their own human rights performance.

Liu Xiaobo’s passing and China’s human rights violations

Foreign governments have the right to complain about the People’s Republic of China’s denial of internationally-guaranteed human rights to the Chinese people. The PRC, for example, in the exercise of its vaunted sovereignty, chose to limit its sovereignty by ratifying the UN Convention against Torture that spells out in detail all the kinds of conduct that constitute internationally forbidden torture, mental as well as physical. The PRC’s mistreatment of its many political dissidents plainly violates this Convention in many respects.

The case of Liu Xiaobo’s widow, Ms. Liu Xia, is an obvious example of the PRC subjecting to forbidden torture someone who has not even been accused of a crime or even legally detained. As to her husband, we don’t know the facts of his final imprisonment and the extent to which he was denied adequate medical treatment but it is widely suspected that the authorities at least demonstrated indifference to his increasingly dangerous medical condition and that its mistreatment of Liu Xiaobo could well be deemed a violation of the Convention against Torture.

Of course, Liu Xiaobo’s criminal conviction was based on the regime’s suppression of his freedom of speech and the violations of criminal justice protections that marked his prosecution. Both of these categories of rights are protected by the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, which the PRC has signed but not yet ratified. The PRC has, however, ratified the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, which requires it to respect the freedoms of expression denied to Liu Xiaobo. It is nonsense for the PRC, on the one hand, to commit itself to international rights protections in the exercise of its sovereignty and then, on the other, to say that holding it to such commitments is a violation of its sovereignty.

Not only should foreign governments condemn China for its violations of human rights that led to Liu Xiaobo’s imprisonment and death, but they should also press the Chinese government to give Liu Xia, who has been put under severe illegal house arrest for the past seven years, the option to leave China. If she chooses to remain in China, the Chinese government should, in accordance with its international human rights obligations, immediately lift all the oppressive conditions that she has suffered.

However, the chance that Liu Xia will be allowed to leave China or have genuine freedom at home in the near future may be slim. The Chinese regime was obviously extremely reluctant to release Liu Xiabo, whether at home or abroad, because of understandable fear of what he would choose as his final words. At home, if he had been allowed to leave the hospital, he would have been kept under strict guard to prevent media contacts, as so many other human rights victims currently are. This is what I call “Non-release ‘release’”. Release abroad would have permitted him to indict the Chinese Communist Party dictatorship before the world, unless the Party insisted on keeping Liu Xia and her brother as hostages.

The PRC is also very sensitive about being seen to allow what it calls “foreign interference with its judicial sovereignty”. As noted above, however, this is a spurious argument in those cases where it has exercised its sovereignty to commit itself to the international standards it has violated.

While it is easy to conclude, given the current relentless repression, that the Chinese Communist Party cares little about what the world thinks of it, I believe that it actually cares desperately, even today. That’s one of the reasons why it confined Liu Xiaobo, despite the great “soft power” cost in doing so. Allowing him to be free would have been even more costly in ”soft power” terms because of his withering criticism. Moreover, it would have allowed him to “subvert” its dictatorship by challenging it on democratic grounds before the Chinese public.

Liu Xiaobo and Liu Xia, cartoon by Badiucao

Liu Xiaobo’s fate: the painful choice of exile or extermination

Liu Xiaobo and his wife Liu Xia at a hospital in China; source: Associated Press

The world has been watching whether Chinese Nobel laureate Liu Xiaobo, who has been diagnosed with last-stage liver cancer, will regain some final moments of freedom in order to receive adequate medical treatment abroad. His friend, Liao Yiwu, wrote a moving tribute (Chinese here) during the weekend, stressing Liu’s wish to leave China with his wife and brother-in-law for medical treatment, preferably in Germany with the U.S. as another possible destination.

Liao Yiwu himself is a splendid writer and also a poet. He is alive and active today because, after enduring harsh punishment in China, he made the decision to go into exile in Germany and, like the Chinese who assembled in Washington, DC and other places outside the Mainland July 9th to mark the second anniversary of the start of Xi Jinping’s continuing 709 purge of human rights advocates, he is free to express his views.

The dissimilar fates of Liao and Liu Xiaobo illustrate the painful choice (if they have that choice) that has always confronted civil libertarians from dictatorial regimes – exile or extermination. Ninoy Aquino, Kim Dae-jung, Annette Lu, Ai Weiwei , Chen Guangcheng and so many others have earned our sympathy and support, whatever their ultimate decision.

Many foreign scholars have agonized with and advised those who have had to confront this decision. The 1979 prosecution of Annette Lu in Taiwan under the KMT caused me to write a very long piece in the Wall St Journal, Asia – “A Taiwan Dissident’s Long Road to Prison” – describing the dilemma in particular of foreign students who choose to strengthen their human rights commitments by studying in democratic countries and then face the dilemma of whether and when to return home to dangerous dictatorships.

When on July 15 legal scholar/activist Xu Zhiyong is released from Chinese prison, I hope he will have the choice whether to stay in China or go abroad for a time. It is far more likely that Xi Jinping will decide to continue Xu’s confinement by other means via what should be called “the Non-Release Release” (NRR) that currently keeps so many supposedly “free” ex-human rights prisoners and their families effectively under political restraints.

On a lighter note, Liao Yiwu’s message reminds me of a passionate lecture he gave in Chinese to a packed house at the New School in NY about five years ago during his first American visit. The first questioner asked him: “What do you think of the U.S,?” Liao answered: “ I’ve only been here four days and I’ve spent them all in Flushing.” Undeterred, the questioner said: “So what do you think of Flushing?” Liao flashed a smile and responded: “That’s easy. Flushing is China without Communism!”

Second Anniversary of the 709 Crackdown on Chinese Lawyers and Activists

Today is the second anniversary of China’s “709 crackdown” on human rights lawyers and activists. ChinaChange published a statement by the The China Human Rights Lawyers Group here.

This statement is sad but important (I almost mistyped “impotent”). It is noteworthy in many respects but two stand out to me. The first is an extensive note of bitterness not only, as usual, against the Party and government responsible for this obscenity but also against the legal scholars, professors and lawyers in and out of government who have lent their cooperation or blessings to the repression.

The second is the absence of any optimistic prediction that, at least in the near future, the numbers of human rights lawyers will be expanding in response to the effort to suppress them. This is a grim, realistic assessment of the situation. Those of us lucky enough to be on the outside can only hope that the programs being held today to commemorate 709 will stimulate greater support for this gallant, besieged group and their families, inside as well as outside China. I share the statement’s confidence that, in the long run, the Chinese pendulum will again swing in the direction of freedom and that the historic role of the human rights lawyers will be vindicated.

Source: China Human Rights Lawyers Concern Group, July 6, 2017

Establish Yourself at Thirty: My Decision to Study China's Legal System in 1960

This is the first chapter that I have written for my memoirs. It has just been published in the Chinese (Taiwan) Yearbook of International Law and Affairs (vol. 33). It tries to answer the question I am most often asked: why and how did you decide to take up what was in 1960 an extremely arcane, indeed an unknown, subject. It also necessarily seeks to provide a picture of the state of Sino-American relations at that time and of American attitudes toward and understanding of what was still called “Red China”. I will eventually give an account of my roots and development prior to 1960 but it seemed most appropriate to start with the decision to study China.

China’s state compensation for illegal detention

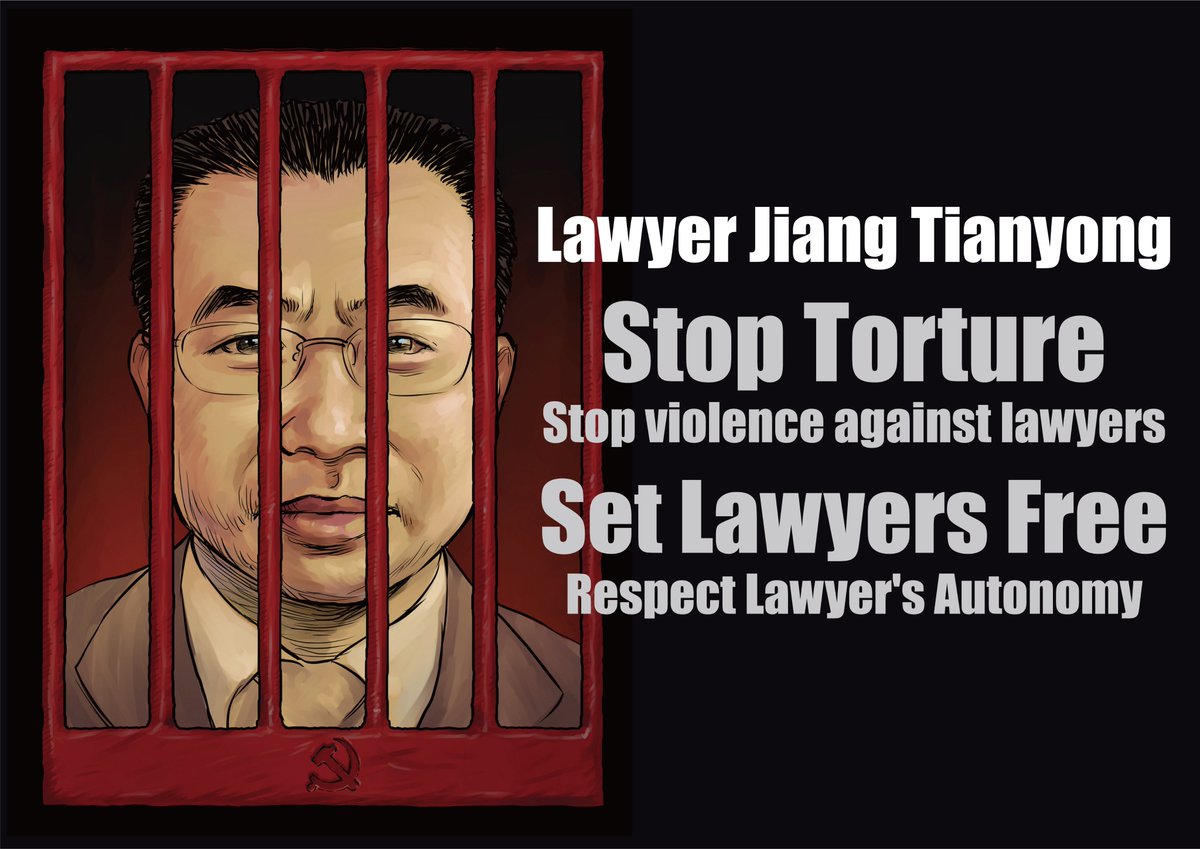

Photo: 中國維權律師關注組 China Human Rights Lawyers Concern Group

Last week we had news that the courageous lawyer Jiang Tianyong has been formally “arrested” after being held incommunicado since last November. It is sadly ironic that, on the same day, the Supreme People’s Court and the Supreme People’s Procuracy announced a new standard for compensating citizens who have been illegally deprived of their personal freedom (see HRIC Daily Brief here). At 258.89 RMB (USD38) per day my friend Jiang may someday receive more compensation than he earned as a great human rights lawyer!

What Ivanka Trump’s company should do for labor conditions in Chinese factories making the brand’s shoes

Here’s a good report by Keith Bradsher looking into labor conditions in a Chinese factory making Ivanka Trump shoes, a sequel to his report on China’s detention of labor activists who went undercover at Chinese factories making shoes for Ms. Trump and other brands.

For the detained labor activists striving to improve working conditions, Ivanka Trump’s company has a moral responsibility to speak out. It would be helpful to the situation of the activists if the company would issue a statement expressing deep concern over their detention. That alone might bring about their release. In any event it would stimulate local police to treat the detained better than otherwise; detention house conditions in China are often appalling with a large number of suspects confined in a single cell in an often disgusting and personally dangerous environment. A Trump expression of concern might well result in a faster, more lenient decision about how to deal with the case.The Marc Fisher company at least made a prompt statement promising to inquire into the facts.

Ivanka’s company has a moral responsibility not only to those detained but also to all workers who are exploited by Chinese companies striving to make a profit while competing with rivals to successfully respond to the demands of foreign companies for ever cheaper prices. It would also be good public relations for Ivanka to take the lead in supporting more humane working conditions. She should not see the human rights monitors as antagonists but as collaborators in the difficult effort to assure improved labor conditions.

Collective Family Punishment - Challenge and Response

Greg Baker/Agence France-Presse — Getty Images

New York Times’ Chris Buckley and Didi Kirsten Tatlow wrote a good story a few days ago about the resistance and resilience of the wives of Chinese human rights lawyers who have been detained.

These recent spousal responses do represent something new because they are frequently collective or joint rather than individual actions as occasionally occurred in the past and also because the Internet and social media offer opportunities for protest that were not previously available.

Moreover, each such spousal protest stimulates others, even in Taiwan. The Mainland protests of Xie Yang’s wife and Li Heping’s wife, for example, seem to have inspired the feisty wife of Li Ming-che, the Taiwan activist who has been detained in China since March 19.

Another new aspect of current protests is a greater willingness of the spouses to go to Washington in an effort to light fires under the Congress and the Executive Branch. Families of jailed dissidents and their jailed lawyers have long fled to the U.S. for refuge, as some oppressed lawyers have also, but, prior to the 2015 crackdown, they did not generally stir up protests here. And recent protests here have not been limited to Washington but have also taken place in New York and other cities, with college-age children often joining mothers whose English is not fluent.

So one might say that Xi Jinping’s resort to collective family punishments, which were formally abolished at the end of the Manchu dynasty, has evoked a collective family response.

Two important developments in China-North Korea relations and another significant DPRK human rights event

Increasing tensions in the North have led to two new under-discussed developments worth noting. The Chinese Embassy in Pyongyang has recently urged its citizens in the DPRK to return home because of the increased danger of attack. According to the May 2 Korea Times, one Chinese who took the warning seriously and returned home reportedly said that most Chinese in the capital were ignoring the message because the atmosphere there seemed peaceful despite the threats emitted in the global crisis. This is the first time such a warning had been issued, according to this informant.

Even more interesting is the April 26 report in Seoul’s “Daily NK” that the government has ordered the police, including the secret police, to “refrain from warrantless arrests” and house searches because such police crackdowns are not in accord with the intentions of the Party and estrange the people from the Party. People reportedly have recently shown intense resistance to the formerly unlimited exercise of police power. There is speculation that the authorities, in anticipation of possible Chinese cessation of oil supplies, may be trying to prevent internal unrest. But this restriction of the power of the secret police has supposedly had an adverse effect on the morale of the agents of the Ministry of State Security since some of them have been purged for apparently not heeding the restrictions out of “excessive loyalty” to Kim Jung-Un.

I have always wondered about how relatively unimportant the problem of illegal search and seizure has seemed to the Chinese people in comparison with other violations by police.

Another human rights event worth noting is the DPRK’s first ever welcome to a Special Rapporteur appointed by the UN Human Rights Council. The Special Rapporteur on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities arrived in North Korea today, May 2, for a six-day tour.

What journalists can do in the case of Lee Ming-che

Here is an article that Yu-Jie Chen and I wrote on China’s secret detention since March 19 of Taiwan rights and democracy advocate Mr. Lee Ming-che. We argue that China’s handling of the case violates Mr. Lee’s human rights and a cross-strait agreement Beijing and Taipei signed in 2009. This incident has dealt a serious blow to the reliability and legitimacy of cross-strait institutions, which is not in Beijing’s interest.

(Voice of America—Wikimedia Commons)

Where is Lee? Journalists, especially Taiwanese journalists, should keep asking questions about his fate, including in the press conferences of China’s Taiwan Affairs Office and the Foreign Ministry. In particular, we still don’t know whether he is detained under “residential surveillance at a designated place” (指定監視居住) or normal criminal detention (刑事拘留) (although as we pointed out in the article, the charge of “endangering national security” suggests that Chinese police may have invoked the former procedure).

If it’s criminal detention, the police can hold the suspect as long as 30 days, by which time they have to ask the approval of the procuratorate to formally arrest (逮捕) the suspect in order to keep him in custody. The prosecutors have up to 7 days to make their decision. The 37-day mark for Lee’s detention is April 25 (counting from March 19). If there is any formal arrest in Lee’s case, it should be made by April 25. At that point journalists should ask whether a formal arrest has been approved. If it has, where is Lee being held? Why? Can he see a lawyer? Will Taiwan officials have access to him?

If there is no formal arrest, Chinese spokesmen should be asked whether Lee is under “residential surveillance,” according to which the suspect can be held for up to six months in an undisclosed place (i.e., without the protections of a formal detention center) and has no access to the outside. Torture is commonplace in such circumstances.

Symbolic dissenting votes of China’s National People’s Congress

Here is a nice Bloomberg report noting the decline of dissenting votes in China’s National People’s Congress (NPC) since Xi Jinping’s ascendance.

In a China Quarterly article written right after the 1978 Constitution’s appearance, China's Changing Constitution, I predicted that the then dormant NPC might not always remain dormant. Gradually, especially beginning in the ‘90s, the NPC came to enjoy considerable life as open struggles developed over important economic legislation such as the Company Law, Securities Law and Labor Law. I came to believe that the journalists’ favorite term for the NPC - “China’s rubber-stamp legislature” – was no longer accurate.

Moreover, the votes on various annual work reports permitted legislators to register their dissatisfaction and criticisms of how the laws were being administered. The number of votes after each report, including those by the Supreme People’s Court and the Supreme People’s Procuratorate, were at least a modest indication of the growth of intra-Party democracy and the seeds of possible legislative independence of the Executive, the Courts and the Procuracy, branches of government that the Legislature in theory is supposed to control.

Since Xi Jinping’s ascendance and particularly today, it is clear that the Party has brought the Legislature to heel as part of Xi’s drive to subject all institutions, including government, the media, the legal profession and civil society, to the Party’s unbending will as he interprets it.

China’s latest legislative effort and the rule of law

Here’s a good report by Josh Chin at WSJ about the new legislation that China’s National People’s Congress is expected to pass next week – a set of general provisions of the Civil Code.

Chinese media generally praise this as a breakthrough in the rule of law. I do think that enactment of part of the forthcoming Civil Code will be an important step in the further development of civil and commercial law in China and promote China’s economic and social development and its business and personal and private interactions with the rest of the world. It will further evidence the important work of legal scholars, law teachers, lawyers and government officials to build a rule of law in China. Since 1978 they have already made major contributions that have helped create a legal environment to foster China’s remarkable economic and commercial progress and its cooperation with the world. In addition, the promulgation of the Contract Law, an impressive achievement, is also one of the building blocks of this evolving system. The Company Law and related legislation should also not be ignored.

Yet those who say it is window dressing are also correct because, while all this drafting, enacting and implementing of civil law-related subjects has been going on, aspirations toward what is popularly understood to be the “rule of law” have obviously been frustrated by Xi Jinping’s increasing oppression of political and civil rights and the arbitrary actions of a police state that has returned fear to the daily lives of many Chinese. The most fundamental aspect of the rule of law is protection against arbitrary detention and imprisonment and other official actions that restrict basic personal freedoms. Here, despite some legislative progress in this area, is where the current regime has ostentatiously failed to respect the rule of law in practice.

Many courageous legal reformers in China today, unable to combat the severe repression, have focused their energies on drafting better pieces of paper – legal rules – especially in the civil area where it has been possible to make progress in practice. Thus one can say that, generally speaking, the PRC has been slowly vindicating the hopes inspired by its ratification of the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights. Yet it is light years away from being able to credibly ratify the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights that it signed so many years ago.

China’s Chief Justice’s Extraordinary Statement: The Most Enormous Ideological Setback for a Professional Judiciary

Here is Flora Sapio’s original blog post about China’s Supreme People’s Court Chief Justice Zhou Qiang’s recent statement, which has provoked some unusual public opposition from China’s law reformers. Several aspects distinguish Zhou Qiang’s new and surprising statement.

It is much more threatening to the judicial cadres than the usual recitation about the importance of following the Party line. It focuses almost exclusively on “morality” and political reliability. Its reference to heroic historical figures is surely bizarre and suggests that the recent investigation of the Supreme People’s Court by the Central Discipline Inspection Commission must have uncovered judges’ lack of reverence for Chairman Mao as well as their continuing desire for judicial independence from Party interference. This statement is the most enormous ideological setback for decades of halting, uneven progress toward the creation of a professional, impartial judiciary. It has already provoked some of China’s most admirable law reformers and public intellectuals to speak out in defiance, and, despite their prominence, I fear not only for their careers but also for their personal safety.

I see Zhou’s statement as possibly necessary in order for Zhou Qiang, an enlightened and progressive Party leader, to have his appointment renewed by the 19th Congress. There is immense dissatisfaction among many judges, especially the younger judges, over Xi Jinping’s restrictive, anti-Western legal values being imposed on them, contrary to their largely-Western-type legal education. This comes at a time when the courts are undergoing reforms designed to reduce the numbers of officials called “judges” by as much as 60% in order to make the remaining judges more of an elite, receiving greater prestige and compensation and a better reputation for competency. Many younger officials are leaving the courts, and the procuracy too, for work in law firms, business and teaching. They do not want to spend their lives applying legal principles opposed to their largely Western-type legal education.

Disappearance of Chinese human rights lawyer: what it means to be placed under “residential surveillance” in China

It’s been reported that (ex) human rights lawyer Jiang Tianyong, who disappeared on November 21, has been placed under “residential surveillance” (RS) by Chinese police. This sad experience shows how the new provision in the 2012 Criminal Procedure Law (CPL) – Article 73 – regarding RS has been abused by the police and the Party.

Lawyer Jiang Tianyong

My hope, rather vain in the current political climate, is that Jiang’s case will ventilate the problem of “residential surveillance” so thoroughly that it will create pressure for reform, as did Ai Weiwei’s case in 2011. At that time, if the government’s target maintained a residence in the jurisdiction of the police, the police were forbidden by Ministry of Public Security (MPS) rules to detain him in any residence but his own, i.e., to restrict him to genuine house arrest. What the police often did, however, as in Ai’s case, was to detain suspects they deemed undesirable in places designated by the police that were neither suspects’ homes nor regular police detention houses that, whatever their failings, were at least regulated by normal criminal procedures and protections. This was a plain violation of MPS regulations if the suspect maintained a local residence.

As a result of the Ai case and others that resulted in protests, when the CPL was revised in 2012 a specific provision was inserted into the new code authorizing RS “at a designated location”, i.e., in police custody, even in cases where the suspect maintained a local residence, but limiting this new authorization to three circumstances, i.e., cases involving national security, terrorism or serious bribery. As is so often the case, the relevant legislative language is vague, especially the provision that permits police to impose this six-months incommunicado sanction whenever they decide that the suspect may have committed a crime related to “national security”, an exercise of discretion that, unlike their desire to formally “arrest” someone, which must be approved by the procuracy within a 37-day period, the PRC system does not permit any other agency to review. Thus, as in Jiang’s case, all they need to do to inflict RS is assert a suspicion that the case might involve some aspect of national security.

Without even meeting any standard such as “probable cause” to believe the crime was committed by the suspect, the police detained Jiang ostensibly because he might have “incited subversion of State power”. This gives the police six months, without interference from any lawyer, family, friends or media, to subject the suspect to a whole range of pressures and punishments including torture in a highly coercive, sealed-off environment.

At the end of that very long period the police decide, based on the suspect’s degree of “cooperation” as well as other factors, whether the evidence elicited via their techniques warrants criminal prosecution in accordance with prescribed procedures leading to “arrest”, indictment, trial, conviction and sentencing. The final formal charge may indeed claim a violation of “national security” such as “subversion of State power” or merely “incitement” to such subversion. But the charge may turn out to be for a lighter offense the long incommunicado investigation of which would not have been authorized by the RS legislation.

So was the 2012 revision a reform? On the one hand, it prohibits police from giving RS in a “designated location” to a local person suspected of tax irregularities, for example, as Ai Weiwei supposedly was. On the other, it now for the first time authorizes incommunicado RS for local people any time the police choose to investigate conduct they wish to claim might constitute a type of “national security” violation (or a serious bribery or terrorism-related case). The result is that police, and the Party, now enjoy virtually unlimited freedom to arbitrarily detain and punish for six months anyone they think may be a dissident. This needs to be kept in mind when considering the progress made by the formal abolition of the police administrative punishment of “reeducation through labor”.

It should also be pointed out that Party members, who are subject to the feared Party “discipline inspection” procedures of “shuanggui”, which can extend incommunicado detention for longer periods than RS, are not immune from RS either, although it would take unpermitted empirical research to determine how often this type of RS is used against them.

China’s seizure of underwater US drone and implications

China has returned the U.S. underwater drone (“unmanned underwater vehicle” or UUV) that it seized in the South China Sea last week. Plenty has been said about the illegality of China’s seizure, such as Julian Ku’s analysis here and that of James Kraska and Pete Pedrozo here. The PRC’s feeble and vague attempt to justify its action legally and the immediate move to return the drone certainly reflect its awareness of its poor legal position.

Politically China is using this incident to make the broader point of seeking to halt U.S. surveillance closer to China in what is plainly China’s Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ), whether or not the PRC’s minority legal position prohibiting EEZ surveillance is acknowledged. The UUV incident is undoubtedly an effort to remind us of PRC objections to what is really “close in” surveillance.

Obviously, the attitude of the Trump administration will be crucial in determining whether the U.S. and China are headed toward military conflict. The U.S. government should devise plans for a more vigorous effort to negotiate detailed understandings about UUV and other surveillance activities. The PRC is likely to continue its resistance to such efforts unless it decides to follow Russia’s example by belatedly acceding to the majority rule permitting EEZ surveillance. Such a change in principle is unlikely in the foreseeable future because of the immediate importance to the PRC of insulating from American scrutiny the movements of its submarines in the South China Sea and because the tides there seem to be moving in China’s favor at the moment.

There is also the broader and even more dangerous problem America faces of continuing to protect Taiwan’s security as tensions mount in the Taiwan Strait. The Taiwan and South China Sea issues are related since they both involve the major question of the extent of the U.S. government’s continuing involvement in East Asia. Will there be any possibility of serious negotiations with Beijing on these matters in the near term? First, the U.S. government will have to prepare a strategy, one that will have the backing of a divided American people long tired of foreign wars but aware of East Asia’s importance to our security, of our accomplishments in the post-WW II era and of our values.

International Human Rights Day

Reports about human rights advocates in China suffering in detention and abuse such as this one on Hada, an Inner Mongolian dissident and this one on rights lawyer Wang Quanzhang certainly inspire feelings of sadness and even hopelessness. Yet the odd thing is that many Chinese human rights lawyers and other advocates continue to enter the fray, even though now fully aware of the potential consequences. Efforts are gradually being made to learn what makes them tick. Infectious Western political ideology? Religion, Eastern or Western? The psychology of martyrdom?

Some even now maintain that the numbers of human rights activists are growing, a claim that is plainly difficult to verify. It all reminds me of the situation in South Korea in the ‘70s under General Park while China was still in Cultural Revolution. The late Kim Dae-jung seemed to be motivated by Jeffersonian democracy, indeed believed that the tree of liberty has to be periodically nourished by the blood of patriots, and was prepared to die for the cause, as he almost did on at least three occasions. He was also a devout Roman Catholic and strongly supported by his highly religious wife. South Korea, well over a decade later, experienced a stressful but largely peaceful revolution, and Dae-jung was liberated, vindicated and empowered.

Prospects for his Chinese heirs seem very gloomy at present. Yet, as we mark International Human Rights Day today, we should admire them, wish them well and hope that the UN Declaration on Human Rights, which was adopted with considerable pre-1949 Chinese input, will soon prevail in China too.

Video of my talk with Scott Savitt about his new book, Crashing the Party, An American Reporter in China

Here’s the video of my talk on November 22 with Scott Savitt about his new book, Crashing the Party, An American Reporter in China, which I highly recommend. Thanks to the China Institute in America for hosting the event and recording it.

Youtube:

Part 1: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5zIjeVjcQ0Y