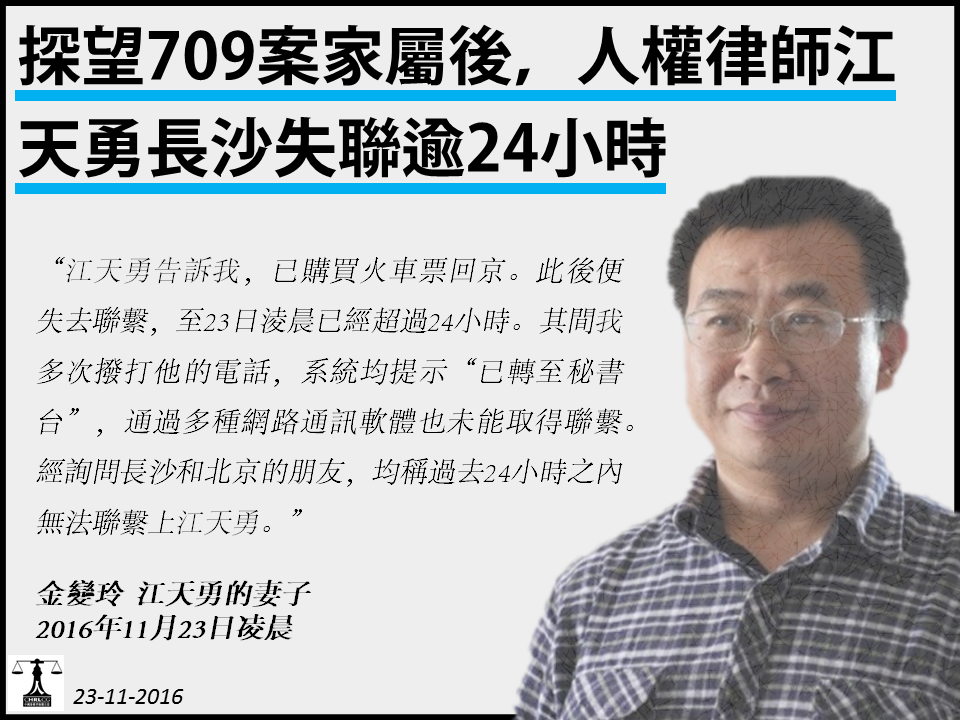

Jiang Tianyong, a prominent Chinese human rights lawyer, was apparently abducted on November 21 after visiting the family of another human rights lawyer who has fallen victim to China’s crackdown starting from July 9 last year (709 crackdown). Jiang’s wife as well as family members of the rights lawyers who have been detained since the crackdown and fellow lawyers have issued a statement demanding the Chinese government to launch an investigation and reveal Jiang’s whereabouts.

Let us hope that Jiang will soon be released. He is a hardy veteran of such intimidations but this time he may be held for much longer than before. The police may have secretly detained him in the guise of “residential surveillance”, which would give them the power to hold him incommunicado for six months if they claim that he falls into one of the three categories of supposedly exceptional circumstances that allow detention apart from the conventional criminal process. Or he may be detained in the guise of the regular criminal process, according to which the police, again because of their very broad interpretation of another narrow legislative exception, allow themselves 30 days to hold a suspect before being required to charge the suspect before the prosecutor’s office or release him. Or, as often happens, the police or their hired thugs may have simply detained Jiang with no legal authority, in effect kidnapping him as they have so many others including one of his early clients, the blind “barefoot lawyer” Chen Guangcheng.

I first met the courageous Jiang in Beijing in 2005 when he and his law partner Li Heping, who has long since been confined as a result of criminal prosecution, were representing Chen, and we all lunched together. Jiang told me at that time how, as a young public school teacher, he had decided to become a lawyer in order to try to improve China’s human rights situation. Shortly after lunch, Chen was abducted by Shandong police who had come to Beijing without seeking permission of their local counterparts.

For more than a decade since that meeting Jiang himself has had to play “cat and mouse” games with the security police in an effort to avoid the long-term detention that would stop his human rights work. For example, a few weeks after Chen’s abduction I telephoned Jiang to tell him that Chen, in a quick, furtive call to me, had asked that Jiang take the night train from Beijing to Shandong to try to visit Chen. Jiang agreed to try, despite the serious risk that he would be beaten by police thugs who were guarding Chen’s village. An hour later, however, Jiang called me back to report that he had received a call from the local judicial bureau ordering him not to travel to Shandong. The judicial bureau had evidently been contacted by whoever had been listening to my first call with Jiang. As a result, he did not make the trip but did manage to send an assistant, who was indeed abused by the local Shandong thugs.

Similarly, some years later, shortly after arriving in Beijing, I called Jiang to invite him to dinner that night. He said he would have to call me back in half an hour because he needed to ask for permission from the police “minder” stationed outside his law office. When he did call me back, he declined my invitation because the “minder”, whom Jiang evidently knew quite well, said that if Jiang wanted to return to the office the next day he had better not see me that night. Jiang, however, told me that his assistant would be permitted to join me for dinner, as he did, undoubtedly under surveillance.

Yet, despite such commendable caution, police have on some occasions detained and abused Jiang, but not for the long term that he might now confront.