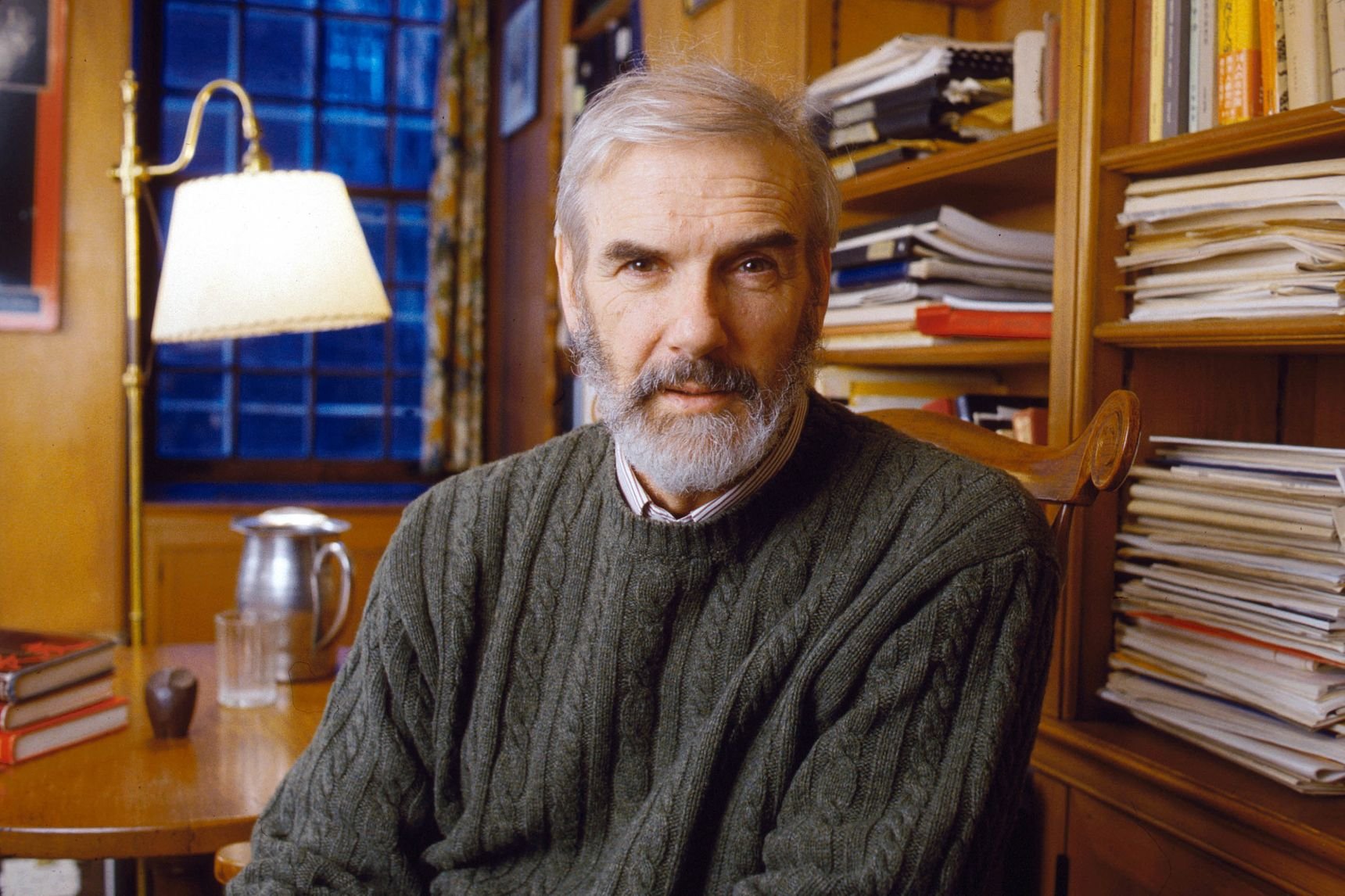

By Jerome A. Cohen

As the significant and widespread obituaries demonstrate, all who knew Jonathan Spence or read his work will greatly miss him and his contributions. I always felt an especial admiration for him because of his appreciation of the importance of China’s traditional legal system and his encouragement of budding historians to pursue this often neglected aspect of the country’s development. In recalling the many splendid books that Jonathan produced, the obituaries that I have seen failed to mention one early work that is worthy of current attention: “The Death of Woman Wang.” Below is my 1978 review for the New York Times Book Review.

A Local History: Review of "The Death of Woman Wang" by Jonathan Spence

CHINA remains a rural nation. Well over 700 million of its almost one billion people live in the countryside. Mao Tse‐tung's genius lay in recognizing that the Chinese revolution's success would turn on the ability to mobilize and transform the peasants. Is the People's Republic succeeding in this Promethean effort?

Foreign observers can form only the most tentative appraisals. Denied sustained and free access to China's million villages, they combine fleeting personal impressions with inferences drawn from publications, radio broadcasts, refugee interviews and other sources. Visitors to communes frequently long to know what really takes place there. What do people actually think? Moreover, the problems of penetrating rural life are not only political but cultural as well, inhibiting the understanding of urban Chinese, not to mention foreigners.

During the century before the triumph of Communism in 1949 foreigners enjoyed expanding access to the Chinese countryside. The accounts of missionaries, traders, travelers, novelists and, eventually, scholars — Chinese and foreign — taught us much about at least some places. K. C. Hsiao's “Rural China in the Nineteenth Century” offered as masterful a set of generalizations as could be made about the vast and varied land.

Yet even then, China was a society in transition. To discern the impact on rural life, first of internal disintegration and imperialist intervention and then of Communist revolution, one has to establish a baseline prior to the changes that the 19th century brought with increasingly bewildering speed. Describing political, social and economic conditions in the hinterland in the pre‐modern era, however, is even more formidable a task than depicting the contemporary situation. One cannot visit the past, and there are no daily newspapers or broadcasts to monitor or refugees to interview. Nevertheless, sources can be found, and Jonathan Spence, a distinguished Yale historian, has skillfully interwoven three — a local history, a magistrate's handbook and a collection of stories by a gifted writer — to re‐create the world of an ordinary Chinese county in the latter part of the 17th century.

Professor Spence, whose previous book, “Emperor of China: Self‐Portrait of K'ang‐hsi” focused on the highest reaches of the social scale, here presents T'anch'eng in the coastal province of Shantung, “a peripheral county that had lost out in all the observable distributions of wealth, influence, and power.” He introduces “the sorrow of its history” not through a Sinological orgy of names, dates and places but by sketching the context and then ushering us into “the zones of private anger and misery” and “the realms of loneliness, sensuality, and dreams that were also a part of T'an‐ch'eng.”

His success offers a Chinese “Winesburg, Ohio,” a series of vignettes and portraits that establishes the common humanity of people separated from us by time, culture and circumstance. If the tone of Sherwood Anderson's tales is sad, Professor Spence's is depressing. Small‐town Americans in the early 20th century were less preoccupied with survival, or even economics, than with universal, intractable human dilemmas. By contrast, the residents of T'an‐ch'eng despite the fact that the newly established Manchu dynasty was approaching the zenith of its splendor played out their individuality amid the devastation, famine and epidemics brought on by recurrent natural disasters including drought, floods, locust plagues and earthquakes. These disasters in turn stimulated human plagues such as corruption, banditry, war and even cannibalism. As the author of the magistrate's handbook wrote of T'an‐ch'eng: “The area was so wasted and barren, the common people so poor and had suffered so much, that essentially they knew none of the joys of being alive.” These were the conditions that elsewhere in China produced periodic upheavals and rebellions that became the antecedents of revolution.

The special social and economic injustices suffered by the women of traditional China added fuel to the fires of revolution. “The Death of Woman Wang” shows us how virtually every aspect of T'an‐ch'eng life reflected their unfair treatment. Female infanticide was common practice, girls were fed less than boys, they were often crippled by foot‐binding that was designed to titillate the male psyche, they were frequently bought and sold to become servants, wives, concubines or prostitutes, they were discriminated against in matters of inheritance, they could not share fairly in property acquired by the family during marriage, husbands could divorce far more readily than wives, widows usually confronted great hardship, and rape was an ever‐present consequence of the countryside's insecurity. Thus, in an area where suicide was a common exit from misery, it is not surprising that women seemed to resort to it even more than men. Confucian pieties proved insufficient restraint in this respect as in others. Indeed, in certain instances, as when a childless widow killed herself out of loyalty to her late husband or a wife chose death to avoid rape, the prevailing ethic considered suicide to be morally correct.

Woman Wang, the character in the last story who lends her name to the book, chose a different escape from an unhappy marriage — running off with another man — and for this her husband eventually strangled her. Because Chinese law regarded a wife's betrayal as a major offense and provocation, he was not sentenced to death but only to a beating with the heavy bamboo and to the humiliation of a long period wearing the kangue,a large and uncomfortable wooden collar that was a badge of shame.

Resentment against the administration of justice also contributed to unrest and Professor Spence reveals the functioning of the imperial legal system at the local level. He adds to our knowledge of the cruelty and corruption of the magistrate's assistants, whose abuses were literally proverbial. He illustrates how official torture sometimes elicited false confessions from the accused, and how the powerful and rich men often manipulated the system through intimidation, bribery and other means. Yet he also shows conscientious and clever magistrates surmounting such obstacles to achieve just results and earn popular respect. Interestingly, this latter aspect of imperial justice, as well as its repressive features, is being emphasized by a traditional‐style opera and film — “Fifteen Strings of Cash” — currently being shown all over China as part of an effort to demonstrate the post‐Mao Govern- ment's interest in protecting human rights.

In fact, almost every facet of Professor Spence's historical account is relevant to those interested in the People's Republic, for, despite the great changes that have intervened, China today faces many of the same problems that confronted her new Manchu leaders three centuries ago,. How to feed people, enhance production, collect revenue, govern efficiently, allocate responsibility between local and central authorities, instill ethics, cope with corruption, curb arbitrary rule, eradicate superstition, reduce rural boredom and enlist popular enthusiasm remain as challenging now as they were then.