By Jerome A. Cohen

The second plenum of China’s 19th Party Congress was concluded last week. It paved the way for amending the Constitution to establish a National Supervision Commission. But this proposed “reform” has encountered fierce misgivings, especially among three expert groups: members of the Procuracy, i.e., the national and local prosecutors; influential scholarly specialists in constitutional law and criminal justice; and human rights and criminal defense lawyers.

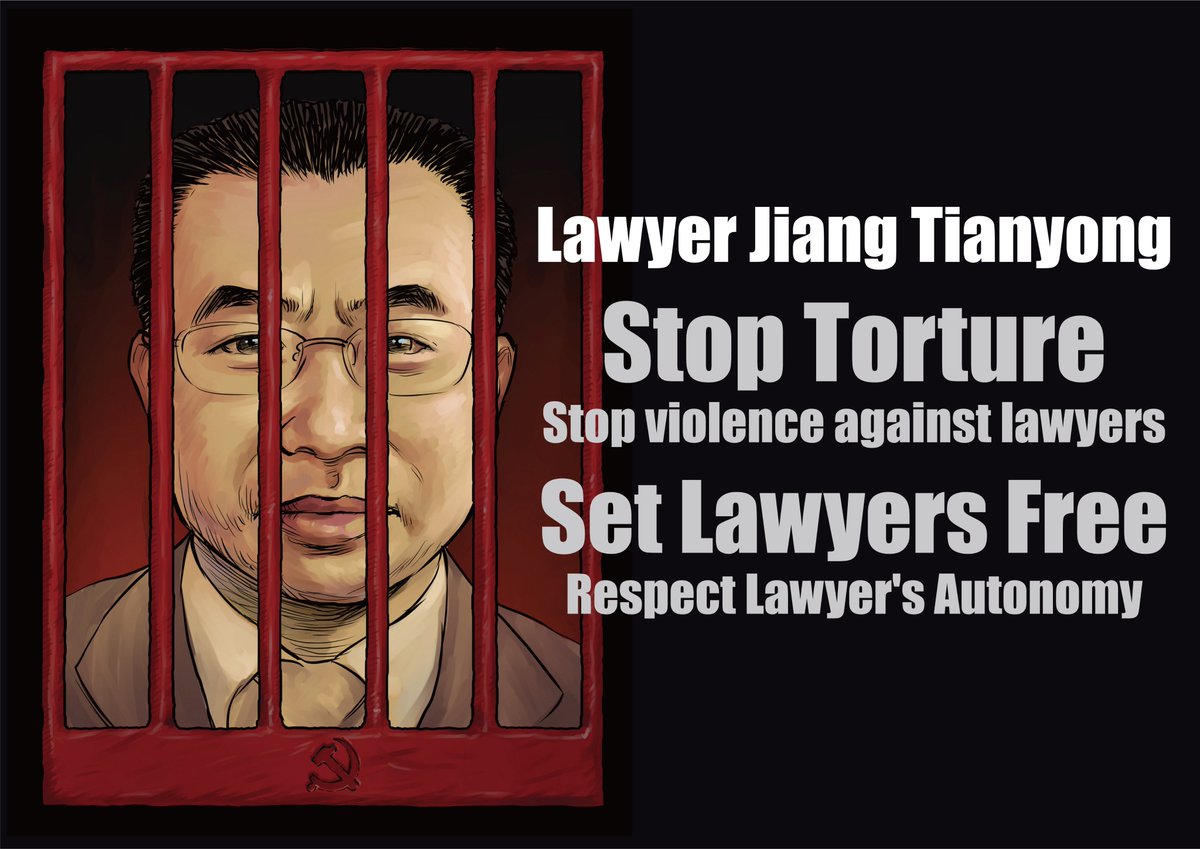

The anticipated Constitutional and legislative changes represent a huge setback for almost four decades of official, scholarly and professional efforts to establish a rule of law that will protect the rights of individuals in their dealings with the government and the Communist Party. The Procuracy has major institutional reasons for opposing the new situation, since many of its personnel will be reassigned to investigative work in the supervisory commissions that will in effect be largely lawless in terms of meaningful procedural protections for suspects. Moreover, the powers of those prosecutors who remain in the Procuracy will certainly be limited in their handling of cases sent to them by the supervisory commissions. Also, procurators, scholars and lawyers are plainly opposed to the changes for many other good reasons including the length of incommunicado detentions possible without any other check or restraint, the absence of access to counsel, the very broad scope of the conduct that can be punished, even going beyond the criminal law’s prohibitions to include alleged violations of Party discipline and public morality, and the very large numbers of people—far beyond only Party members—who will be subject to repression and fear.

These changes will create a nightmarish scenario that will counteract many of the genuine reforms to the criminal justice system that are being developed and currently discussed. Yet, after a courageous academic protest meeting drew harsh official reaction, no one has dared to speak out in a public way despite great hostility to the changes continuing to be expressed on a confidential basis.

Xi Jinping regards formal authorization of these changes, which have already taken place in practice in many places, as positive because it will give an official fig-leaf to a terrifying investigatory/punishment process that until recently has been largely practiced by the Party against Party members and that has been widely condemned as lawless by many critics at home and abroad. But this new attempt at official veneer is plainly not authentically legal, even in terms of the government’s existing legal system. The anticipated constitutional amendments cannot remedy the situation and will make major alterations in the governmental system that the People’s Republic imported from the former Soviet Union..

What is at stake here is the legitimacy of the country’s legal system in the eyes of the educated, articulate but currently silenced, influential elites. Political leaders, bureaucrats, business figures and their employees, prosecutors, judges, legislators, professors and especially lawyers have good reason to fear that they may be the next victims of a plainly arbitrary system. This is the Inquisition with Chinese characteristics!