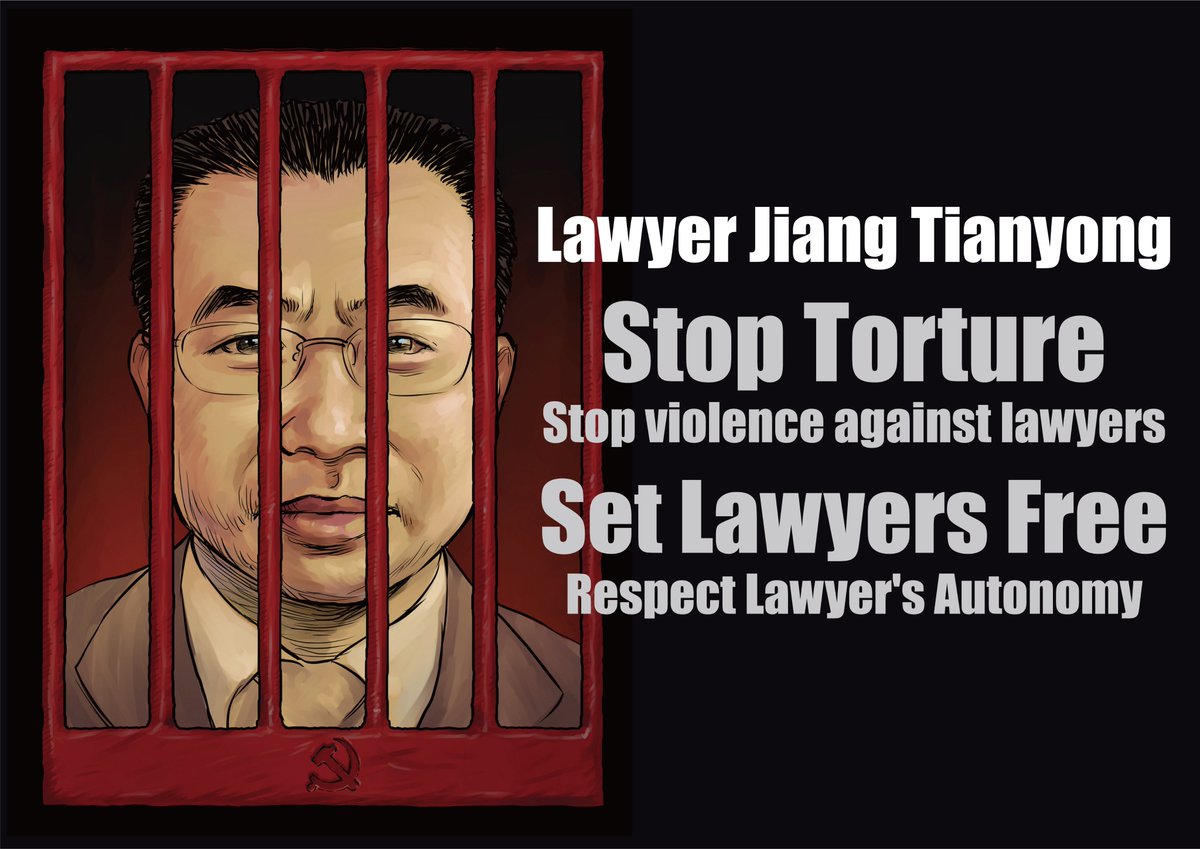

Jiang Tianyong was sentenced to two years on the charge of “inciting subversion of state power.” His prosecution/persecution has been a tragic farce from the day he was detained a year ago.

Jiang was a primary school teacher who decided that he could do more for his country if he studied law and learned how to defend human rights. After doing so he became a partner of the dynamic human rights lawyer Li Heping, and I met them both at a lunch meeting with their client, the blind “barefoot lawyer” Chen Guangcheng, just, a couple of hours before Chen was literally seized by Shandong police who came to Beijing without notifying their local counterparts. Chen was about to meet with the then Washington Post reporter Phil Pan.

Li Heping was prosecuted earlier than Jiang, was convicted and served terrible prison time before being “released” in a now typical NRR (“non-release release”) and is now inaccessible while recovering at home.

Li’s younger brother, Li Chunfu, also became a human rights lawyer and met the same fate as the older brother on whom he had modeled his career. Li Chun-fu was “released” from prison before his brother and returned home a virtual vegetable suffering from severe mental illness induced by his prison experience, where he had been forced to take debilitating drugs in the guise of (un)necessary medicine for non-existent illness.

Jiang Tianyong, despite disbarment, was able to elude formal detention for a longer period than the other lawyers and still be helpful to detained human rights advocates and their oppressed families. Jiang knew how to work within the limits for a long time. I recall inviting him to dinner one night in Beijing before the 709 campaign began. He said “I’ll have to call you back to confirm in half an hour, since I have to go outside and ask my security police minder for permission”. He later called back and said that the minder told him “If you want to go to the office tomorrow, you should not go to the dinner.” So instead he sent an assistant. This was an illustration of the restrictions on many human rights activists that might be termed PDD (“pre-detention detention”)!

Another, more ordinary pre-detention restriction of Jiang’s freedom was earlier illustrated when Chen Guangcheng, after his forced return to his rural home, was subjected to severe house arrest. Chen telephoned me in Beijing and asked me to persuade a lawyer to travel to his Shandong village that night in an effort to break his illegal confinement. I telephoned Jiang Tianyong, who agreed to book a train ticket. He later called me and said that the police, having listened to our phone conversation, had forbidden him from making the trip. At least that spared Jiang the beating by village thugs who, under police guidance, always used violence to prevent outside contact with Chen.