Liu Xia holds a portrait of Liu Xiaobo during his funeral. AP: Shenyang Municipal Information Office

The propaganda struggle over Liu Xiaobo’s demise was a sad but fascinating spectacle. The PRC’s distorted video broadcast of his medical examination was a ghoulish sight as well as a horrible invasion of his privacy and violation of arrangements made with the German government. The truncated, swift and restricted funeral arrangements were a farce.

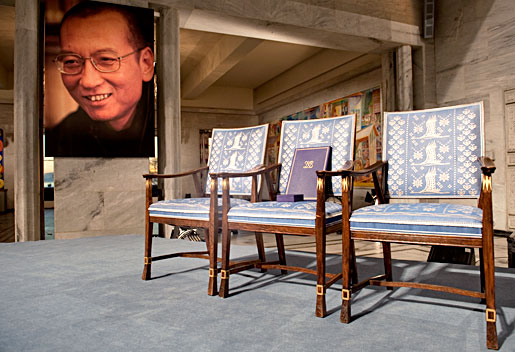

Yet, as some observers have come to recognize, if only as inadequate consolation, the extraordinary circumstances of this Nobel laureate’s departure may prove his greatest contribution to the cause of free speech he so gallantly served. Liu’s final tragedy has alerted the world, to an extent even greater than did the empty chair in Stockholm, to the Chinese Communist Party’s inhumane oppression.

Despite the enormous international pressures on Xi Jinping, China’s ruthless leader insisted on Liu’s last pound of flesh. Xi was bent on heartlessly punishing Liu to the end for following the admonition of Xi’s own father, a famous first generation Communist leader who, after suffering 16 years in political exile, urged the Party to allow freedom of speech not only among the elite but also for all Chinese people. Today in China such advice constitutes “incitement to subversion.”

In terms of its immediate impact, Liu’s death has energized human rights activists outside China, at least for a time. Unfortunately, however, I don’t think his death will have a major favorable impact on human rights activities inside China, since he had already been silenced for a long time and most people in China don’t know about him, at least in a positive way. To the extent people do know about him and care, many will be further intimidated by his fate, while some others may be inspired to enter the human rights field, if only cautiously.

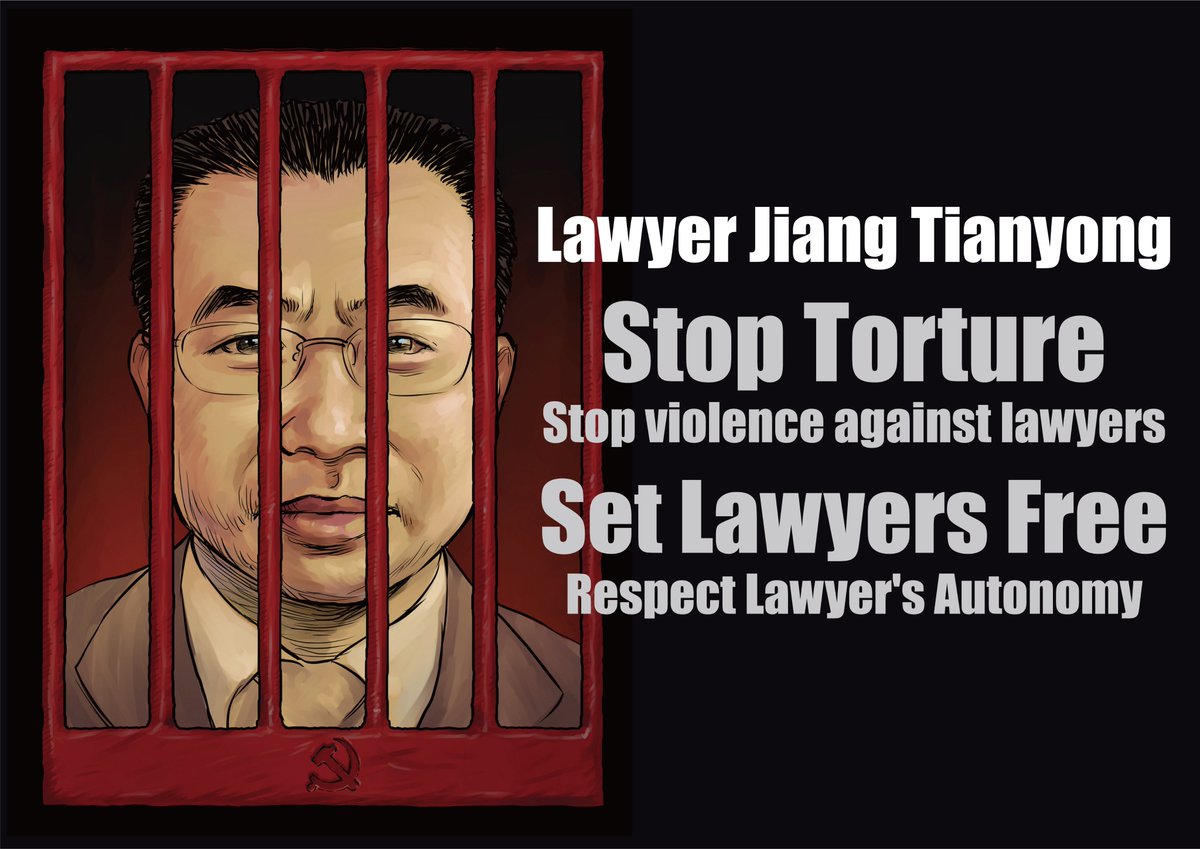

On the surface the human rights/political reform movement in China is in dreadful shape. It obviously has got this way because of extraordinary massive, ruthless and efficient repression that has understandably deterred the many liberal elements in Chinese society and government. Yet, quietly, quite a lot of professional legal reforms are still under way. They do not affect the many political prosecutions that take place or the unauthorized, illegal restrictions that are indefinitely imposed on human rights activists, outside the formal legal system, by police and their thugs. But they gradually improve procedures in ordinary criminal cases and lay the groundwork for more comprehensive reforms to occur when the political climate becomes less repressive, as it may well after Xi Jinping’s eventual departure from office.

Human rights issues will not disappear from the media with Liu. The cases of his wife Liu Xia and just released from formal prison Xu Zhiyong will highlight what I call NRR – “Non-Release ‘Release’”, another, lesser-known but insidious form of oppression. These are home prisons of an indefinite duration, and they restrict not only the activists but also their families, relatives and friends. Usually there is no legal authority for such repression. Ask Cheng Guangcheng, Gao Zhisheng, Li Heping and Li Chunfu, for example, or their families! There are too many examples.

When Liu Xiaobo was treated in the hospital, Chancellor Angela Merkel called upon the Chinese government in vain to release him to go abroad for his final moments “as a signal of humanity”. Can we expect foreign governments to do more? Will they be more effective? Many governments feel that their human rights protests against Beijing will have no positive impact on the PRC and will have a negative impact on other aspects of their relations with China. To the extent they do protest, it is often more a response to their own citizens’ pressure for action than to genuine concern for human rights, and their domestic business constituents usually have more clout than their human rights community. Compassion fatigue and realistic hopelessness about the Xi Jinping regime are also factors.

Yet those of us on the outside have to persist in our efforts to directly influence developments in China and to put pressure on our own governments not only to influence China but also improve their own human rights performance.