Here’s a good report by Josh Chin at WSJ about the new legislation that China’s National People’s Congress is expected to pass next week – a set of general provisions of the Civil Code.

Chinese media generally praise this as a breakthrough in the rule of law. I do think that enactment of part of the forthcoming Civil Code will be an important step in the further development of civil and commercial law in China and promote China’s economic and social development and its business and personal and private interactions with the rest of the world. It will further evidence the important work of legal scholars, law teachers, lawyers and government officials to build a rule of law in China. Since 1978 they have already made major contributions that have helped create a legal environment to foster China’s remarkable economic and commercial progress and its cooperation with the world. In addition, the promulgation of the Contract Law, an impressive achievement, is also one of the building blocks of this evolving system. The Company Law and related legislation should also not be ignored.

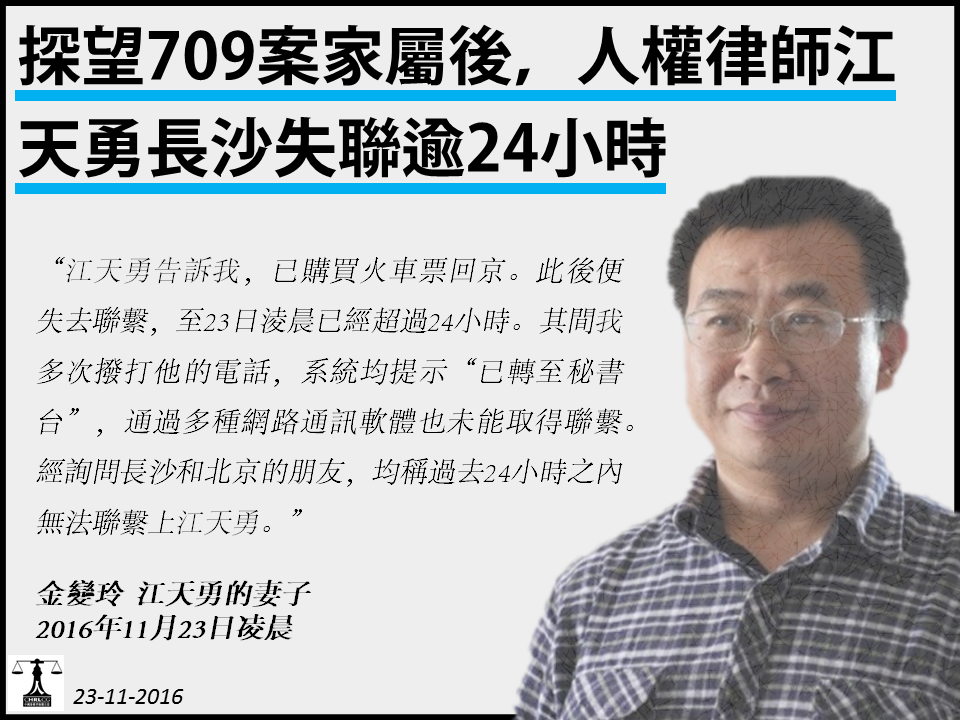

Yet those who say it is window dressing are also correct because, while all this drafting, enacting and implementing of civil law-related subjects has been going on, aspirations toward what is popularly understood to be the “rule of law” have obviously been frustrated by Xi Jinping’s increasing oppression of political and civil rights and the arbitrary actions of a police state that has returned fear to the daily lives of many Chinese. The most fundamental aspect of the rule of law is protection against arbitrary detention and imprisonment and other official actions that restrict basic personal freedoms. Here, despite some legislative progress in this area, is where the current regime has ostentatiously failed to respect the rule of law in practice.

Many courageous legal reformers in China today, unable to combat the severe repression, have focused their energies on drafting better pieces of paper – legal rules – especially in the civil area where it has been possible to make progress in practice. Thus one can say that, generally speaking, the PRC has been slowly vindicating the hopes inspired by its ratification of the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights. Yet it is light years away from being able to credibly ratify the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights that it signed so many years ago.