Human Rights lawyer Teng Biao, Photo credit: May Tse/South China Morning Post

Here is a stimulating op-ed by Chinese law scholar and activist Teng Biao. I hope US funders, public and private, will take it into account. I believe, after giving due regard to Teng Biao’s admonition against funding the oppressors, funders should continue to support those non-Chinese institutions that do not pull their punches in studying and reporting on legal developments in China while also continuing to conduct legal and human rights education of not only Chinese lawyers but also Chinese judges, prosecutors, justice officials and even police.

The point that needs greater recognition here is that hundreds of thousands of legal specialists in China are extremely unhappy with Xi Jinping’s oppressive policies, policies that they feel forced to live with and practice while awaiting a less repressive regime and the renewal of true legal reforms. At a time when they are being ordered to reject universal human rights values, we should not abandon these silent supporters of the rule of law, but should keep up contacts and professional nourishment that will sustain them until a better day dawns.

Years ago, the late Senator Arlen Specter asked me to emphasize this point in a letter to then House Majority Leader Nancy Pelosi, recalling the importance of foreign funded legal education and training given to officials of the Chiang Kaishek dictatorship in Taiwan and the Park Choon-Hee dictatorship in South Korea. Those efforts paid rich dividends when political circumstances permitted legal liberalization. Indeed, they helped fuel legal officials’ opposition to dictatorship, as occurred when Taiwan prosecutors and judges rebelled against their masters and successfully established their independence of political interference.

The U.S. Congress, other countries and private foundations should also fund basic research on the many complex aspects of the evolving Chinese legal system, not only education and training in China but also efforts to enhance foreign understanding of both contemporary events and the country’s political-legal culture.

In addition, there is a great need to fund the support and activities of the increasing number of Chinese refugee lawyers, law professors and human rights activists who, like Professor Teng, are turning up outside China as a result of the terrible situation they confront in China.

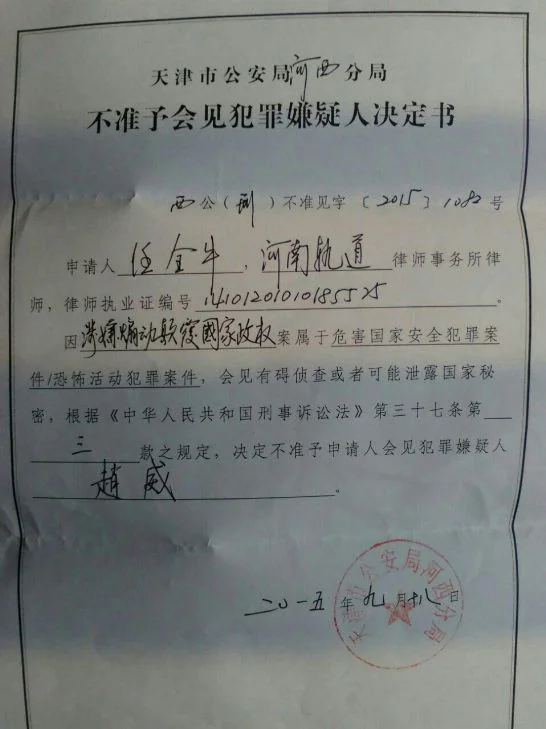

Finally, in fairness to the America Bar Association, we should note that, after long internal debate spawned by external criticisms, it has decided to establish an international human rights award and next week at its annual meeting in San Francisco this new award will be bestowed, in absentia, on another of China’s courageous human rights lawyers, Ms. WANG Yu, who, sadly, is jailed in China and awaiting criminal conviction and a long prison sentence.