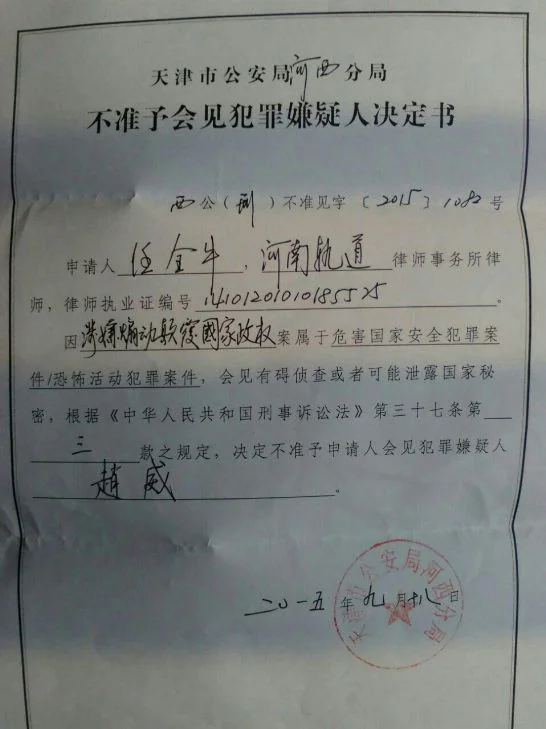

My colleague Yu-Jie Chen has just sent around her comments below on the police’s written decision to reject the lawyer-client meeting (“不准予会见犯罪嫌疑人决定书”) in recent cases related to the oppression of lawyers and other human rights advocates since July 9 last year (“709”). With her permission, I’m pasting her comment below, followed by my response.

“This kind of decision to reject the lawyer’s request to meet with the criminal suspect seems to have been standardized into a form and used in several cases of the 709 activists and lawyers, including lawyer Wang Yu (here), Li Heping’s 24-year-old assistant Zhao Wei (here), law scholar Liu Sishin (here), and activist Wu Gan (the latest 不准予会见 decision in his case was issued on Feb. 6). All these decisions have been issued by Tianjin City public security authorities (including its Hexi branch), which has been in charge of the 709 crackdown as far as I know. In addition, the case of lawyer Zhang Kai, who has been detained in Wenzhou, also saw such a document issued by the Wenzhou police (here). I’m sure there are many others that I haven’t seen.

The basis invoked by the police is Article 37 (3) of the Criminal Procedure Law, which, in cases involving crimes endangering State security, terrorist activities or significant amount of bribes, asks defense lawyers to obtain the approval of investigating agencies before meeting with their clients.

However, we should note that in the September 2015 regulation issued by the Supreme People’s Court, Supreme People’s Procuratorate, Ministry of Public Security, Ministry of State Security and Ministry of Justice to protect lawyer’s rights to practice (“关于依法保障律师执业权利的规定”), the police are required to provide reasons (说明理由) in rejecting the lawyer-client meeting. I don’t think simply producing a form as a formality meets this standard. But in reality, I wonder if there is any remedy for such a violation.”

Written notice rejecting the request of ZHAO Wei's defense lawyer to meet with Zhao

Written notice in WANG Yu's case

The use of such a form reveals the cavalier manner in which the police violate their nation’s Criminal Procedure Law by arbitrarily denying the right to counsel in their attack on rights lawyers and other human rights advocates whom they have detained. Indeed, the police are doing exactly what Article 9 of the major September 2015 Five-Institution Regulation interpreting the 2012 Criminal Procedure Law explicitly forbids. They are failing to give lawyers requesting a meeting with their detained clients the reasons for rejecting the meeting.

They simply fill in the bare details identifying the case on a printed police form that claims the requested meeting would interfere with their “national security” investigation OR reveal state secrets, without giving any facts or justification of such alternative claims. This flies in the face of Article 9’s stern admonition that investigating agencies may not interpret “as they wish” the “national security” and other exceptional provisions authorizing them to deny counsel their right to meet detained clients in certain circumstances. This admonition, based on decades of experience demonstrating how in practice the police always turn narrow legislative exceptions into broad arbitrary rules, is specifically designed to prevent the police from arbitrarily restricting the right of lawyers to meet their detained clients.

According to the law, lawyers should be able to vindicate their rights by seeking administrative review of the police refusal at the next higher police level and by asking the local procuracy to investigate the arbitrary police refusal. Such efforts are apparently being made but no one is holding his breath in the expectation that this will bring relief. For example, over 15 years later I am still waiting for the office of the Supreme People’s Procuracy in Beijing to send me its promised report reviewing the lawless detention of a Sino-American joint venture’s Chinese CFO by the city of Jining in Shandong Province.

In most cases, initially and repeatedly, police denial of lawyer access to detained clients seems to be orally communicated. Issuance of a written form seems to be done belatedly and reluctantly as part of a customary effort to block or at least delay any review of the decision.

The Hexi District Sub-Bureau of the Tianjin Public Security Bureau seems to have attracted a very large number of detention cases related to the 709 crackdown. I note that the September 18, 2015 Decision denying her lawyer’s access to young Ms. ZHAO Wei is numbered 1,082 for the year!!! That does not mean that the huge number of such cases that preceded it last year were all 709 cases but it seems likely that many of them were such supposed “national security” cases. And we do not yet know how many more such cases occurred last year after September 18. Moreover, there may be some double counting since defense counsel sometimes try a second time later in their client’s detention. The Five-Institution Regulation authorizes the meeting of lawyer with client in alleged “national security” cases once the meeting will no longer prove an obstacle to investigation or the risk of revealing state secrets is gone.